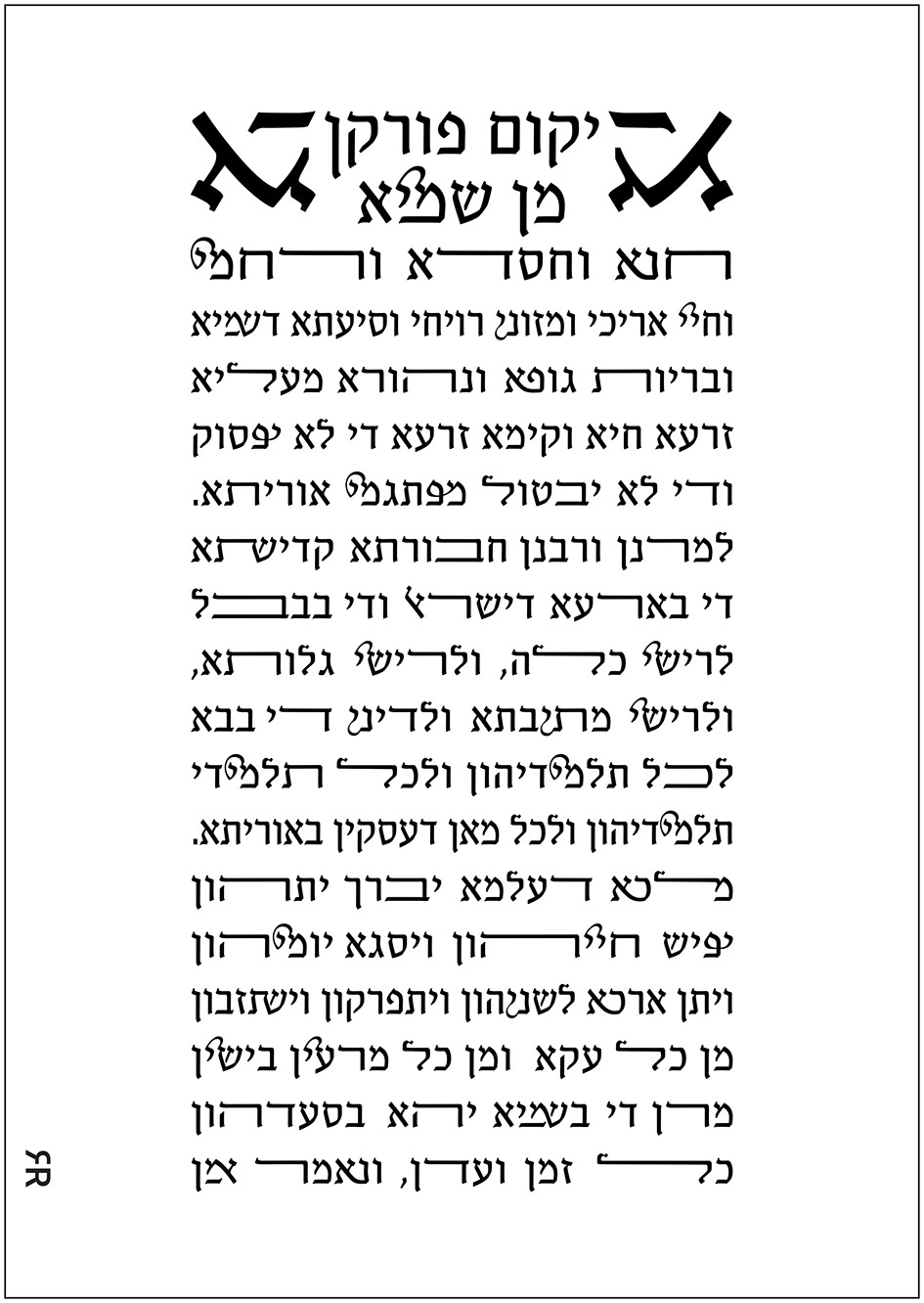

Why Yekum Purkan Doesn’t Include Our Soldiers (And Should It?)

Recently, much discussion has centered around the role of Charedim in the army, often veering into side debates. These include questions like - is someone who appears Charedi entitled to take a vacation during wartime? or should institutionalized Torah study continue at all when the nation is at war? Such debates reveal the underlying tension between different segments of our society and reflect deeper questions about values, priorities, and responsibilities.

This issue came to my attention more personally last week when an influential rabbi shared a post expressing frustration over Charedim enjoying time in the park during their vacation while his son in the army is rarely given time off. The post was filled with emotion and understandably so, but I felt it was missing a constructive path forward. I feel it is imperative to bridge our differences and focus on that which unites us rather than what divides us, as I wrote about in an earlier post.

I commente…